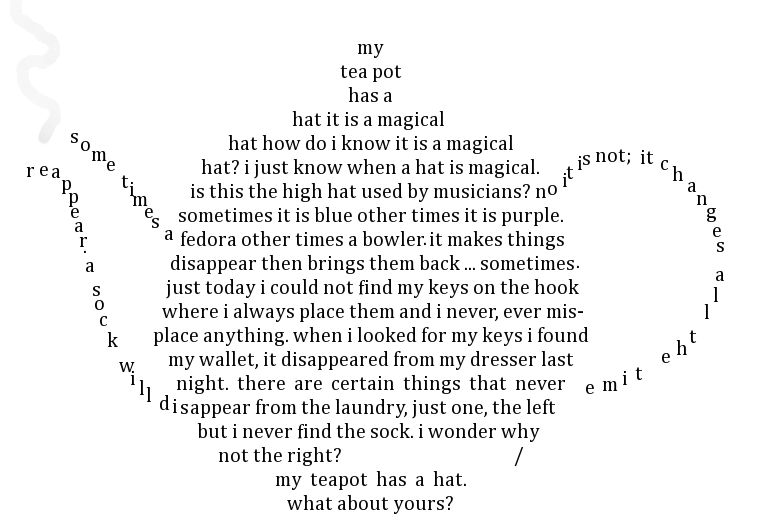

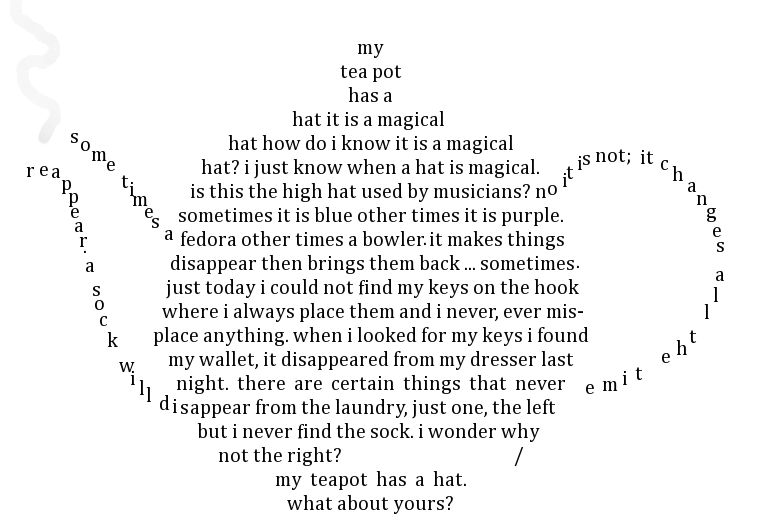

Teapot

MPR – online and print poetry journal for the new now

Teapot

New Worlds

a planet of marigolds / stippled yellow flames against the sky / & all of these flowers swiveled their frilled faces / as i fractured the middle of one’s stem / & wore it behind my ear / running barefoot / & joyous in the soft soil / until the petals preserved in brown fragility like bog bodies mummified in peat / exploded as crushed glass flashed lightning in the downpour / sweeping away all vegetation rooted in the cratered rock :: i hid under large leaves & slept with the hard stem in my hands / until blue light streamed from the cracks / between the leaves / & opened them up to rainbow flowers / floating in midair / as if the atmosphere had turned to water / because the motion was that fluid / as petals & leaves drifted past me :: sometimes i still see the white plastic of female mannequins surface on farmland after the rain / but their auburn hair had fallen from their scalps / & regrown as milkweed for the monarchs / monarchs fused with metal / the size of wolves :: i hung my wet cotton dress on a sturdy tree branch / & splashing my cheeks in a puddle / noticed it took longer for the water to reflect the motion of my hands & thickness of my thighs / they warped in & out of their shape / as i stood above the puddle / who is this person :: there is a rumor carved into the bark of a felled tree that evrythin hppns fr e resn & Gd hs e pln fr u & maybe that explains strange mouths made from dust gathering up in the fields / telling me of cities bubbling back into the ocean / & plastic mountains reaching for a face lit in the moon :: i collected the body parts of mannequins dug up & washed them off to sew up a new woman / a complete woman / who leans against a tree / she has a blue eye / green eye / red torso / white face / & blue limbs :: green-sequined ferns curl toward her in the night / & a rumor in my dreams says naked thighs disturbing white sheets were objects of fascination for those who clung to bodies like magnets :: i wear a rusted crown because it fits well on top of my black hair curling up from saltwater / & others wear crowns of thorns / even when all is burnt away into white ash

In Fields of Sunflowers

1. a windpipe was crushed with large fists / & small fists scraping forearms / a bearded chin / cracked white chalk like road salt under a moon cut into slices

2. a woman spread raspberry jam thick on her tongue / & spit a thousand gelatinous seeds down your sore throat with a daring kiss

3. a steel kitchen knife rusted while a black beetle crawled over the dead sheen / leaf litter buried them both under farm dirt

4. little brown-haired children used to run barefoot in these fields of sunflowers / their dirty sneakers kicked off in the shade / screams echoed for miles of blue skies

5. an emerald wine bottle with the neck snapped jaggedly had nurtured a mossy mat over the shards / unrolling over a lone boulder

6. serrated red leaves made little dark patterns on the pure / creamy skin of a small woman’s body slumped against a tree / dark curls swept across her face / hands folded

7. her nails grew a millimeter / her fingers blistered into crocodile marble

8. she thumbed the cool surface of a light bulb / blackened over its curves / & tightened her fist around it until crushed into silver dust / metallic wires tracing circles into her flesh

9. the green spine of a sunflower tunneled up the rings of her trachea / driving between the gap in her buck teeth / & struck a match for a solar eclipse / encircled by red lips

Roses

three severed heads of roses dried in a little crystal box carved with diamonds / pyramids / invisible except to a little girl’s fingertips running along the surface / a box gilded / gold engraved with ancient daisies which refer to day’s eye / wide open to the electric glory of a thousand thousand colors pixelating a single blade of grass / arching into the mud :: your mother dried three roses from her wedding because she wanted three children / because she fell weeping for waxen cadavers displayed in glass cases / because roses are always dead in our gracious hands :: roses are not the roots planted deep in the earth / not the congregation of flowers on a bush / but necessarily severed body parts in a watered vase / & as beautiful as a young woman gently wading in a blue river / wind blowing her long skirt :: you are not a little rose contained / with your palms pressing pink against the glass until la petite mort withers into dreams of rising from the ashes of burnt fields :: you are a thousand daisies opening under the sun / your entire body surging with red until the world saturates starless because you die a thousand thousand deaths / not a quiet little death in a box :: these three roses have shattered so slowly with our light breaths burning their petals each time the box opens / the air is too thin in this box smelling of breastmilk / & vulture carcasses shred apart in the desert :: once you were a little girl who fell asleep under the floorboards in a game of hide-and-seek / & the hands of God painted your eyes like a moon glittering where no one thought to look in a world consumed with darkness :: your memories as a little girl were like metallic pearls under your tongue / spit into your palm / buried with your bare hands in dark soil / turning back into sand :: sand does not have to come from pearls / soil does not have to come from roses / but we can play-pretend with a blank canvas

Stay Awake

in a dream you snapped the stem of a rose in half / silver fluid dribbled onto my soiled palms / you said drink / drink vitamins extracted from thin air / an infant with polished ceruleite irises suckles at my breast / you said wait for the last drop / drop of silver poured down my throat / striping into microscopic vessels / you said there would be a chance your soft caress carries over to the star-speckled fissure between life & death / can you imagine bodies / without bodies / severed from their nerve-fibered fabric tethered to some kaleidoscopic earth / without blue skies snared in our baggy lungs / without skulls like cast-iron pots hunching over our shoulders / without pulsated fluttering of green mantle metalmarks / overshadowed by two large ivory breasts spread apart in the sun / between life & death can we become lanterns without metal frames / bursts of raw stone without direction / you said stay awake you have to promise me you’ll stay awake. i said i’ll try but words are sometimes only words. a black-haired woman opened her armpits / a garden curling with fresh roses / all her petals peeled off into a simple glass vase / once you read on the internet that jupiter has seventy-nine confirmed moons / & so softly you held these playthings spinning rainbows / diluted magenta / on gravel / beneath your feet / you stockpiled all seventy-nine in your left palm as i wept / once you were a child who dove into a black hole in the frozen lake / a crowd broke into applause muffled as you pierced the surface / you almost opened your mouth for the cold water / to flood the emptiness in your chest / you counted the seconds / the seconds you could hold your breath / the seconds before water ripples with moonbeams from above / moons orbit around your body like a school of fish / you weren’t sure whether you’d ever been loved / i wasn’t sure if i’d ever be loved / stay awake you said. stay awake. / sometimes your mouth opened for a butterfly to crawl out / with wet wings / not yet ready to muscle into flight / sometimes you screamed out / a thousand of them / surging into the galaxy / sometimes an infant unlatches from my breast to stare straight into my eyes / silver milk trickling from his mouth / i stared back at myself / my underwear had become wet with thick blood streaming down my thighs / which is to say i am a woman / which is to say i am no longer a child / i am still a child / i was never a child / tell me a story you haven’t told me before you said as you held me in your lap / unbraiding my damp hair as i fell asleep to your heartbeat what if i could tell you what happens next / would you believe me

About the Poet

Christine A. MacKenzie received a B.A. in English, creative writing and psychology from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. In fall 2020, she will start an MSW in Interpersonal Practice to become a psychotherapist. She has been recently published in Susquehanna, The Inflectionist Review, Red Cedar Review, Fourteen Hills, and The Merrimack Review.

Family Work

3 A.M. Lok-Yiey rose from

her bamboo bed, rubbed kindling,

blew and blew on embers, ashes on

her cracked face and dried gray hair.

She boiled rice in red clay pot,

diced garlic, minced pork,

fried morning glories.

She placed the bamboo pole

on her shoulder,

different dishes on each side,

and rushed to the train station

in Monkulburi, Battambang.

“I did what I must,” she says,

“To keep you from hunger.”

Decades later in America, my uncle

made eggs and toast for his kids,

rice gruel with salted fish

for himself and his wife.

He dropped his children at school,

his wife at the train station in Malden,

then drove to the video store in Chelsea.

He converted anyone who walked

through the door with his smile,

“Good morning, Sir” or

“Good evening, Madam.”

When asked about his seven-day

work schedule, he told me,

“When the Khmer Rouge made you

dig ditches and carry mud in the sun

all day, everyday, until your body trembled

in fever, everything after is clear as vision.”

This past week in Wakefield

to celebrate her son’s wedding

my aunt and her sister fried rice,

made spring rolls, marinated wings,

dressed papaya salad

in fish sauce, lime, and chilis,

argued with one another.

Seeing them stressed, I suggested

ordering food from a local vendor.

Her answer, “My great joy is

seeing my son and his American wife

eat the food I make. See their happiness

come from these hands.”

The Leaves are Bright Red

There’s nothing else to say about autumn.

Chanda swings from the monkey bar.

My wife’s at home resting, carrying our second child.

The sun so warm and bright on my face,

my cracked hand and grey hair. And I fear growing old,

leaving my children to fend for themselves.

Job prospects, war, and the sun burning a hole

in the ozone, cancer cells eating the scalps of children

and grandchildren. We must listen to Greta Thunberg.

We must do something. Chanda falls off the swing.

I run to pick her up and put her on my shoulders.

The sun warms. The leaves are bright red.

Shivering. Ghosts everywhere

shaking branches. Howling.

I’m trying to cherish this moment, my health,

Chanda’s laughter, the baby in my wife’s womb.

About the Poet

Bunkong Tuon is a Cambodian-American writer and critic. He is the author of Gruel, And So I Was Blessed (both published by NYQ Books), The Doctor Will Fix It (Shabda Press), and Dead Tongue (a chapbook with Joanna C. Valente, Yes Poetry). He is a contributor to Cultural Weekly. His poetry won the 2019 Nasiona Nonfiction Poetry Prize. Tuon teaches at Union College, in Schenectady, NY.

The Water

I hear the water in the basement—

it’s different than the water

on the sidewalk, on the grass:

it thinks, it remembers, it asks why

we haven’t moved away, what keeps us here

year after year, mopping and hoping,

straining our shoulders

against it.

All May it rained upriver,

brought the farmers of Nebraska

to their knees until they seemed

like statues caught in prayer forever,

until their corn, sagging from skyweight,

died away. All June we waited

for the River to concede and let it go.

We no longer pray;

we know we live in an unfortunate world,

surrounded by whim and words

like maybe. We’ve gathered

what we need to be within it—

our pills and trinkets, dollar bills

in plastic bags, the silk fan

my mother brought from Hattiesburg

after the war.

Rear-view Mirror

I bought a car

that promised paradise and sex

and maybe being forgiven

for my multitude of sins.

I bought a car to take me all the way

to Oklahoma, California.

I bought a car

and thus the first of several

forays into danger. In Iowa

a woman called Sue

harangued me with notions of Mars

and “new plantations.”

No idea. Where Omaha meets

the highway again I asked

a listless, righteous Baptist for directions.

Friends: we’re slowly dying

in our automobiles, pivoting through

Kansas, making the Great Plains

smoky and obtuse. I was,

of course, a boy who hoped for

paradise and sex, knowing clutch

and power steering, Madeline and Denise,

Margaret and May. A church glowed

at dusk on the Utah border. A man

emerged, an American flag

in his hand attached to a stick,

a sign touting Pancake Breakfast,

the Armory on Sinclair Avenue, $5.

I drove on. Somewhere Sadie was America,

all lip gloss, root beer, and need.

A blowjob, nobody’s disappointed.

In a room at the Rattler Inn, maybe

Boise or maybe Montana, I turned the TV

to Channel 4, the better world emerging.

A chef in Kansas City, a chef in Traverse City.

I love you, America.

I bought a car and came so far

it seems the only dream’s

the dream of being elsewhere.

About the Poet

Carl Boon is the author of the full-length collection Places & Names: Poems (The Nasiona Press, 2019). His poems have appeared in many journals and magazines, including Prairie Schooner, Posit, and The Maine Review. He received his Ph.D. in Twentieth-Century American Literature from Ohio University in 2007, and currently lives in Izmir, Turkey, where he teaches courses in American culture and literature at Dokuz Eylül University.

Dance as Cubism or Dance as Film

The beauty of dance is the body

executing movements that it can do

while giving the impressions of that

which it cannot do being always

on the edge of the impossible while

maintaining art and joy and flow

seeing the dance from a single viewpoint while having the impression of seeing it from multiple viewpoints as in a cubist painting

dance being an art of movement

in vehement opposition to stasis

in the imagination of traveling in a rotation around the dance and seeing every single angle but in motion not locked as in a Braque canvas

with every piece in place even while

“showing” or “giving the impression” of showing

all aspects at once

as if from different camera angles

as to why dance is better on film

spinning into every possibility.

About the Poet

Paul Ilechko is the author of the chapbooks “Bartok in Winter” (Flutter Press, 2018) and “Graph of Life” (Finishing Line Press, 2018). His work has appeared in a variety of journals, including West Trade Review, As It Ought To Be, Cathexis Northwest Press, Otoliths and Pithead Chapel. He lives with his partner in Lambertville, NJ.

Din of Deafness

The empty hallway stretches between them, filled with echoes.

He arches his neck, creases his brow, as though that would make sense

of the meaningless sounds bouncing from the walls.

She strains to make him understand, her hopeless cries

turn shrill and the hallway lengthens, resounding

with pieces of syllables, howling vowels, no consonants.

He shrugs in anger, as if it were her fault he cannot hear,

then retreats into isolation; she withdraws into her shell.

Two lonely crustaceans divided by silence.

About the Poet

Ellen Dooling Reynard spent her childhood on a cattle ranch in Jackson, Montana. Raised on myths and fairy tales, the sense of wonder has never left her. A one-time editor of Parabola Magazine, and co-editor of A Lively Oracle: A Centennial Celebration of P.L. Travers, Creator of Mary Poppins (Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation, 1999), she is now retired and lives in Nevada City, California where she writes fiction and poetry.

An image in three parts

§1

Then, feeling there was no other way

to go through life, I wrote a confession

§2

From myself having been hidden by nerves,

a voice took up, made a dwelling in me.

I wrote until I saw and felt ashamed.

But just as often I would give way to

some image offered by nostalgia,

which in its fading seemed suffused with light.

The next day, feeling entirely false,

I would have to begin writing again,

would catch myself there with gaze turned elsewhere.

What is out there would appear in transcripts

of private impressions— there, myself,

always being put at a distance so

that touch, which brought to me in its own light

a category of the natural,

could be true— as it is already

in the contours of life as it is lived.

All that plate glass through which the world to life

is brought close— out there what is meant by will.

§3

I am moved by Renoir’s Alfred Sisley:

The right shoulder estranged from bright nature

(being out beyond the open window),

but the left offering hope of dissolve.

A way of living already in place,

I have kept myself close to where I am—

never allowing it to approach me,

touch me and thereby reconfigure me;

What place in me could contain there

§1

I have lately made a career reading

about the problem of self-consciousness.

Sitting down early to work, it becomes

doubtless that I will die without knowing,

still waiting for me to come to myself.

There have been depths constituted in me

by turning from my surface, that mere ground—

having long been afraid of what spirit

dwells in me, what kind of soul takes shape from

an irregular flow of sensations.

When it visits, I am overtaken—

having had too much coffee or having

been sedentary, unmoved, for too long

—until it departs of its own accord.

Then I feel it is some concept, some thought,

that forms life: the world as is, what is there

without understanding, terrifies me.

When I can exhaust my body in work

and it is merely felt, without cover,

I—in that moment of revelation;

of feeling my hand move in the darkness,

like soil being turned over again

—long to have been there always, opened out.

§2

I was shown an autobiography

and have been reading it for nearly four

years now: This work, in which I find the truth,

pulls me from myself into a clearing.

I have waited for each volume, and have

read the most recent one impatiently

in my backyard, at a splintered table,

sometimes losing my place because a gust

of cold air reminds me that I cannot

forget to plan for Christmas holiday.

My dog moves through the yard with her nose to

the ground, sensing the coming of a new

year in the smell of matter passing on—

a smell, I find myself hoping, distinct

from the carcasses of birds, which she hears

as well. What speaks in them I do not know.

Near the end of undergraduate work,

when something new in me had begun, I

read Schelling’s treatise on human freedom:

—We will struggle to remain in the light

once we feel the depths from which we have been

lifted into existence, he writes there.

More than all I have read, this remains true.

Schelling wrote this in the context of an

ongoing metaphysical debate:

In the sense Spinoza meant, is God here?

Schelling posits an original will,

made objective, open, in works of art.

In art our will, desire, confronts us;

in what we make, the divine is with us.

Augustine, when young, took into himself

different heresies moving throughout

God’s creation. One day, in a garden,

he heard the Lord in the words of Saint Paul,

to whom the divine appeared as a light.

Between Paul and Augustine the divine

had been reduced to the words of the Saints,

and in the time of Luther it will speak

only in the quiet of our conscience;

a voice without a throat in the stillness.

The will of God becoming—change—weighs on

the future Saint: If the Lord is perfect

and the world merely his manifesting

his will, why do things develop in time?

Augustine believes the mystery will

be resolved if he can focus his thoughts,

withdraw them from here below. He writes, as

an act of prostration, the Confessions.

§3

Often there are weeks (once an entire

February) in which, out in its midst,

I find I am only myself, morning

bringing relief in the work to be done.

Whatever is physical about the

world—whatever is equally expressed

in the equation and the feeling of

cold when I push myself out into the

morning—persists in spite of what I think.

Should I give way to the force of life or

should I disavow it as unholy,

it will be there still; as though life moves in

a shoal, land having given way to drift.

A few weeks ago, I woke to vomit.

It continued for a few hours, and

then it finally eased. I made my way

to bed and put on music to calm me,

but it made me weep like some old mystic.

This thing which I am—the atom, the string,

a bit of matter turned back on itself—

had come apart and would remain apart.

Longing, I called out of work and ordered

the Upanishads; they now reside on

a shelf my eyes pass over when I sit

down to work unread, before I focus

my gaze on the laptop in front of me.

It makes me ashamed when I see it there.

A reminder that I will struggle to

find myself again in light and that I

won’t care for the light once I am in it:

a recess where the soul takes itself up.

Astral / Insignia

something fragile

undone

something fervent

shunned

we’re often

mistaken for others

looking for a mind

other than this

it became clearer

in the thaw of spring

it became clearer

in that quarrel inside of you

the interior of those moments

doused in forbidden aims

we planned to circumvent

the chaste flames

they lived as we did

in a language that held us

a spell of rain

made me notice the blushing sky

some simple pain

falling into the crevice of my mind

it is hard to ignore

the brook and ravine

the heath and meadow

revealing the stain between

something articulate

and ill framed

Self-Portrait

Looking past

the dissonant flowers

my body comes apart

in stilted frames

Serenading the ancients

we’re pounds of flesh

inhibiting the

warmth of discord

The sprawling pain

like seamless

impassible walls

separates each revelatory day

Finding ways out of

my skin proves difficult

the years levitate

about our inherited clay

To exist is

a brief fit of ambivalence

a dance in

subterranean tombs

About the Poet

J.L. Moultrie is a native Detroiter, poet and fiction writer who communicates his art through the written word. He fell in love with literature after encountering Fyodor Dostoyevsky, James Baldwin, Rainer Maria Rilke and many others. He considers himself a literary abstract artist of modernity.

Years pass and I thought I had landed safely.

But then an unscheduled flight of memory pilots me to that place I vowed never to visit again.

And there I am with the same baggage I unpacked years ago, landing at the same gate, greeted by Larry, the same limo driver.

“Welcome back,” he smirks. “Will you be staying long?”

“No, not this time, I tell him.

“That’s what you said last time,” he replies.

“ I know.” I say.

I excuse myself to use the airport restroom and immediately book a return flight.

Last time I drove with Larry he took me out of my way and then claimed it was to avoid all that inconvenient road work.

I told him I have been gorging on hope.

He said, “you need to monitor that, because hope deferred will make your heart sick.”

Turns out he was right. The next day Hope decided what I really needed for a season was a diet of disappointment.

“It would be good for you” he said. You’ll thank me for it later.”

Sure enough, overnight the promises I once fed on began to taste like hospice haute cuisine —those pimento cream cheese tea sandwiches they serve as afternoon snacks to the terminally ill.

My heart went on a hunger strike.

They forced fed me with an intravenous solution of positive placebos and eventually released me.

But something happened last night last night amid the movable feast of the unforeseeable—hope showed up at my door with a three topping 16 inch pizza.

Turns out he had the wrong address.

It was for Lucille, my next door neighbor, who recently lost her husband Mike to pancreatic cancer.

I was happy the pizza was for her. She too had suffered a diet of disappointment for a season.

Five minutes later she called and asked if I would like to help her eat that pie.

Of course I said yes.

We ate. We talked.We laughed. I actually liked the pineapple topping. With every bite we both felt an appetite for hope rise up within us, like one of those self rising pizza crusts they advertise on television.

Speaking of crusts, Lucille remarked how the crust on our pizza tasted nothing at all like those awful hospice haute cuisine tea sandwiches.

And I had every reason to believe her.

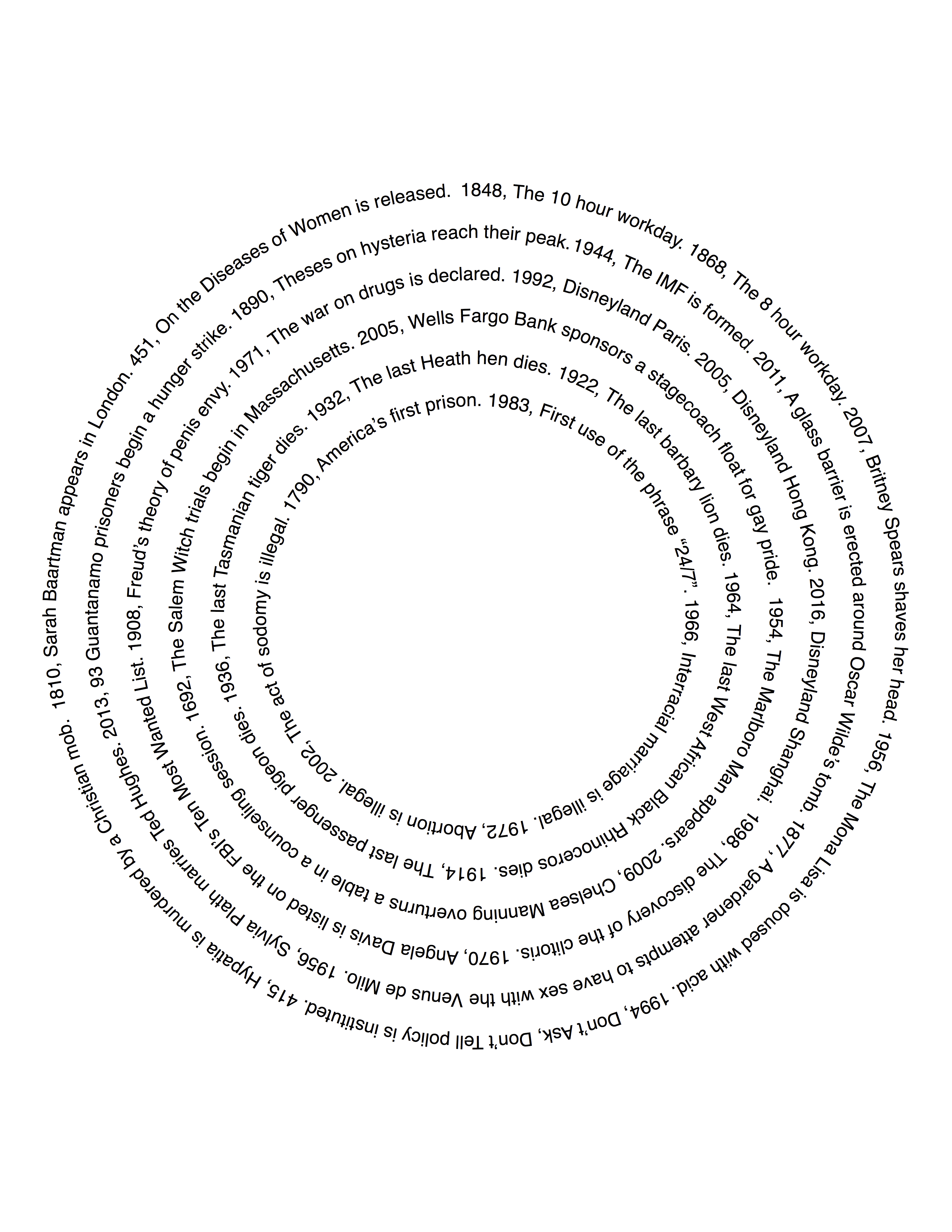

Column

Historical Consciousness

About the Poet

Steph Smith is an interdisciplinary artist working in the mediums of poetry, textile, video, and performance. She currently works in the studio of David Byrne in NYC. She has published 4 books of poetry and a lot of zines. She is curious about power, identity, and trust.